Video of the Week:

Dividing Iris

Upcoming Events:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/k-state-flower-field-day-tickets-26105824223

July 30 K-State Research & Extension Center Horticulture Field Day, Olathe

http://www.johnson.k-state.edu/lawn-garden/horticulture-field-day.html

August 4 Kansas Turfgrass Field Day, Manhattan

https://turffieldday.eventbrite.com

Vegetables:

Heat Stops Tomatoes from Setting Fruit

It usually takes about 3 weeks for tomato flowers to develop into fruit large enough to notice that something is wrong and an additional week before tomatoes are full size and ready to start ripening.

Though there are "heat-set" tomatoes such as Florida 91, Sun Leaper and Sun Master that will set fruit at higher temperatures, that difference is normally only 2 to 3 degrees. Cooler temperatures will allow flowers to resume fruit set. (Ward Upham)

Spider Mites on Tomatoes

Look for stippling on the upper surface of the leaves as well as some fine webbing on the underside of the leaves. These tiny arthropods (they are not true insects) are often difficult to see due to their size and their habit of feeding on the underside of leaves. If mites are suspected, hold a sheet of white paper beneath a leaf and tap the leaf. Mites will be dislodged and can be seen as tiny specks on the paper that move about.

Spider mite control can be challenging. A strong jet of water can be used to remove the mites but may not be as easy as it sounds. A high-pressure directed spray is needed to dislodge the mites. Since spider mites feed on the underside of the leaves, the spray is most effective if it comes from below. This can be difficult to accomplish with a thumb over the end of the hose.

Some gardeners use a water wand hooked to a shut-off valve. The water breaker is then replaced by a brass nozzle. Horticultural oils and insecticidal soaps (Safers, for example) can also be helpful. Spray early in the morning when temperatures are cooler and plants have rehydrated. Resprays will likely be needed. (Ward Upham)

Fruit:

When to Pick Peaches

Peaches that are mature enough to pick are still hard. They do not give when lightly squeezed. However, these peaches will ripen off the tree and will have very good quality. They may not be quite as sweet as a tree-ripened peach but are still very good. So what do we look for to tell if a peach is mature enough to harvest? Let’s look at a couple of factors.

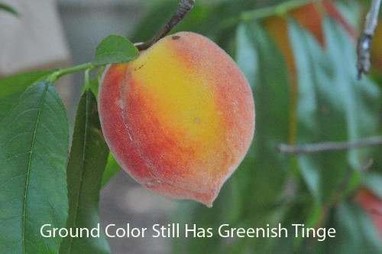

Color: The reddish coloration is not a good indicator. Look instead for what is called the “ground color.” This is the part of the peach that does not turn red; for example, around the stem. The ground color of the peach will lose its greenish tinge and turn yellow when the peach is mature enough to harvest. I use this characteristic more to determine when NOT to pick a peach. If there is any green in the ground color, it is too early. If the ground color is yellow, then I move to the next characteristic.

Ease of Removal: A mature peach will separate easily from the branch if the peach is lifted and twisted. If it doesn’t, it is not mature enough to pick yet. All peaches will not be ready to pick at the same time. Pick only those that are ready and come back later for more. It often takes 3 to 5 pickings to harvest a peach tree.

Peaches that are picked early but will be used for fresh eating should be allowed to ripen inside at room temperature. Once they are ripe, they can be refrigerated to preserve them for enjoyment over a longer period of time. (Ward Upham)

Pests:

Green June Beetles: Out-and-About

The green June beetle has a one-year life cycle, and overwinters as a mature larva (grub). Adults emerge in late-June and are active during the day, resting at night on plants or in thatch. The adults produce a sound that resembles that of bumble bees. Adults will feed on ripening fruits and may occasionally feed on plant leaves. The male beetles swarm in the morning, “dive bombing” to-and-fro above the turfgrass searching for females that are located in the turfgrass (they are desperately seeking a mate). Females emit a pheromone that attracts males. Eventually, clusters of beetles will be present on the surface of the soil or turfgrass with several males attempting to mate with a single female (I think this qualifies as an “insect orgy”). Mated females that have survived the experience lay a cluster of 10 to 30 eggs into moist soil that contains an abundance of organic matter. Eggs hatch in about 2 weeks in early August and the young larvae feed near the soil surface. The larvae feed primarily on organic matter including thatch and grass-clippings; preferring soils that are excessively moist. Larvae are 3/8 (early instars) to 1.5 (later instars) inches in length, and exhibit a strange behavioral trait—they crawl on their back. (Raymond Cloyd)

Flowers:

Dividing Iris

Iris may be divided from late July through August, but late July through early August is ideal. Because iris clumps are fairly shallow, it is easy to dig up the entire clump. The root system of the plant consists of thick rhizomes and smaller feeder roots. Use a sharp knife to cut the rhizomes apart so each division consists of a fan of leaves and a section of rhizome. The best divisions are made from a double fan that consists of two small rhizomes attached to a larger one, which forms a Y-shaped division. Each of these small rhizomes has a fan of leaves. The rhizomes that do not split produce single fans. The double fans are preferred because they produce more flowers the first year after planting. Single fans take a year to build up strength.

Rhizomes that show signs of damage due to iris borers or soft rot may be discarded, but you may want to physically remove borers from rhizomes and replant if the damage is not severe. It is possible to treat mild cases of soft rot by scraping out the affected tissue, allowing it to dry in the sun and dipping it in a 10 percent solution of household bleach. Make the bleach solution by mixing one-part bleach with nine parts water. Rinse the treated rhizomes with water and allow them to dry before replanting.

Cut the leaves back by two-thirds before replanting. Prepare the soil by removing weeds and fertilizing. Fertilize according to soil test recommendations or by applying a complete fertilizer, such as a 10-10-10, at the rate of 1 pound per 100 square feet. Mix the fertilizer into the soil to a depth of 6 inches. Be wary of using a complete fertilizer in areas that have been fertilized heavily in the past. A growing number of soil tests show phosphorus levels that are quite high. In such cases, use a fertilizer that has a much higher first number (nitrogen) than second (phosphorus). (Ward Upham)

Ornamentals:

What's in a Name?

This is a teachable moment, however, and I wanted to take the opportunity to clarify that the common name “Anglojap” does not reference a racial slur of any kind. As with many plants, it references its geographic place of origin. “Anglo” comes from “anglicus” meaning “From England; English.” Taxus is native to Japan, Korea and Manchuria, thus the second part of the common name references “japonicus” or Japan. Taxus xmedia is a hybrid of Taxus baccata (English Yew) and Taxus cuspidata (Japanese Yew) and has been in production with the common name Anglojap Yew since 1900.

Resources to help understand plant names include, of course, Michael Dirr’s “Manual of Woody Landscape Plants.” Another interesting book is A.W. Smith’s “A Gardener’s Handbook of Plant Names: Their Meanings and Origins.” Fun tidbits from the “A” section of this compendium include:

acanth [ak-anth]

In compound words signifying spiny, spiky, or thorny.

Acanthus [ak-AN-thus]

Greek name meaning thorn. In America it is called “bear’s breech” from the size and appearance of the leaf which is very big, broad, and distinctly hairy. The acanthus leaf was a favorite decoration in classical sculpture, as in the capital of the Corinthian column. In England the bear has been dressed up and it is now called “bear’s breeches” despite long-standing authority to the contrary.

Bear’s Breeches (Acanthus mollis) is an herbaceous perennial hardy in zones 6 to 10 and is marginal in Kansas. The species name “mollis” means “Soft; with soft hairs.” So the entire Latin name describes the plant leaves: they are large, broad, and covered with soft hairs. This is to say nothing of the flower on bear’s breeches, which is a quite lovely, bold spike of maroon and white that look somewhat like snapdragon flowers and can rise two to three feet above the foliage. Other species of Acanthus include Acanthus spinosus (spiny leaves), Acanthus hungaricus (from the country of Hungary, native to the Balkans, Romania, Greece) and Acanthus montanus (pertaining to mountains, native to Western tropical Africa). Some of these names remind me of the spells in the Harry Potter universe—not so different from the English names with which we’re familiar.

Back to the “A” section and I’m learning lots of plant history. Take Abelia for instance:

Abelia [ab-EE-lia]

Ornamental shrubs named for Dr. Clark Abel (1780-1926), who, at the suggestion of Sir Joseph Banks, accompanied Lord Amherst on his embassy to Peking (1816-1817) as botanist. Much of his collection was lost by shipwreck on the way home to Kew. Except for Russian ecclesiastical mission, no European naturalist was to visit China for nearly thirty years thereafter, Robert Fortune (see Fortunella) being among the first to follow. Abel died in India while serving as personal physician to Lord Amherst, who was by that time Governor-General.

I love history! I am always interested in learning about the lives of people who were passionate about similar things. The entry on Fortunella was quite interesting…and long. Robert Fortune (Scottish horticulturalist and plant collector) was a rather well-traveled man in the 1800s (China, India, United States). Most other entries in A.W. Smith’s book are descriptive of origin (“chinensis” = “Chinese”) or botanic characteristic (“serratus” = “saw-toothed” or “hippocastanum” = “Latin name for the horse-chestnut. There is a clearly marked horseshoe under the leaf axils.”). A few are just really informative related to the historical importance of the plant or people involved in discovering and naming them. As a side note, I have colleagues who regularly go on plant collecting trips so I’m aware that plant names are still being determined in present times. I’m sure taxonomists will continue to delve deep into the appropriate nomenclature as time goes on. Even in my own relatively short time as a horticulturalist I know several plants for which the scientific name has been changed (and in some cases, changed back!).

Suffice it to say, there is much more to know about scientific plant names, their meanings and origins. However, I hope this narrative provides some perspective on the primary common name of such a common landscape plant in our region as Anglojap Yew. Naming a plant is an honor and never meant to cause harm or disrespect. Often their names even include warnings as in firethorn, Pyracantha coccinea, which means “thorns with scarlet fruit.” Just make sure to steer clear of Toxicodendron radicans (a toxic plant with rooting stems—poison ivy) or Ilex vomitoria (yaupon holly—great landscape shrub actually, just, you know, don’t eat large quantities of it, okay?) this summer.

The aforementioned publication has been updated in the electronic file on the KSRE Bookstore, for those of you wishing to have a new copy. We’re grateful for folks who take the time to let us know when something like that needs to be repaired. (Cheryl Boyer)

Contributors: Raymond Cloyd, Extension Entomologist; Cheryl Boyer, Nursery Crops Specialist; Ward Upham, Extension Associate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed