Video of the Week:

When to Harvest Eggplant

Upcoming Events:

| July 30 K-State Research & Extension Center Horticulture Field Day, Olathe http://www.johnson.k-state.edu/lawn-garden/horticulture-field-day. html |

| August 4 Kansas Turfgrass Field Day, Manhattan https://turffieldday.eventbrite.com The field day program is designed for all segments of the turf industry - lawn care, athletic fields, golf courses, and grounds maintenance. Included on the program are research presentations, problem diagnosis, commercial exhibitors, and equipment displays. There will be time to see current research, talk to the experts and get answers to your questions. Pesticide recertification credit in 3B is available, as well as GCSAA education points |

| August 15 K-State Vegetable Research Field Day, Olathe http://hnr.k-state.edu/events/2016%20GG%20Vegetable%20Research%20Tour.pdf |

Vegetables:

Tomatoes Slow to Ripen?

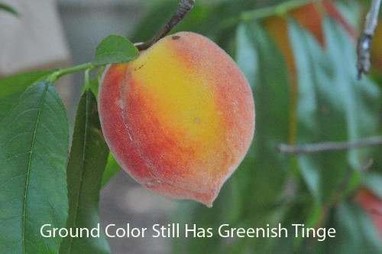

Tomato color can also be affected by heat. When temperatures rise above 95 degrees F, red pigments don't form properly though the orange and yellow pigments do. This results in orange fruit. This doesn't affect the edibility of the tomato, but often gardeners want that deep red color back.

So, can we do anything to help our tomatoes ripen and have good color during extreme heat? Sure, there is. We can pick tomatoes in the “breaker” stage. Breaker stage tomatoes are those that have started to turn color. At this point, the tomato has cut itself off from the vine and nothing will be gained by keeping it on the plant. If tomatoes are picked at this stage and brought into an air-conditioned house, they will ripen more quickly and develop a good, red color. A temperature of 75 to 85 degrees F will work well. (Ward Upham)

Bitter Cucumber

Two compounds, cucurbitacins B and C, give rise to the bitter taste. Though often only the stem end is affected, at times the entire fruit is bitter. Also, most of the bitter taste is found in and just under the skin. Removing the stem end and the skin can often help salvage bitter fruit.

Bitter fruit is not the result of cucumbers cross-pollinating with squash or melons. These plants cannot cross-pollinate with one another.

Often newer varieties are less likely to become bitter than older ones. Proper cultural care is also often helpful. Make sure plants have the following:

– Well-drained soil with a pH between 6.0 and 6.5. Plenty of organic matter also helps.

– Mulch. Mulch helps conserve moisture and keeps roots cool during hot, dry weather.

– Adequate water especially during the fruiting season.

– Disease and insect control. (Ward Upham)

How to Pick a Ripe Melon

When choosing a melon from those that have already been harvested, look for a clean, dish-shaped scar. Also, ripe melons have a pleasant, musky aroma if the melons are at room temperature (not refrigerated). Watermelons can be more difficult and growers often use several techniques to tell when to harvest.

1. Look for the tendril that attaches at the same point as the melon to dry and turn brown. On some varieties this will need to be completely dried before the watermelon is ripe. On others it will only need to be in the process of turning brown.

2. The surface of a ripening melon develops a surface roughness (sometimes called “sugar bumps”) near the base of the fruit.

3. Ripe watermelons normally develop a yellow color on the “ground spot” when ripe. This is the area of the melon that contacts the ground.

Honeydew melons are the most difficult to tell when they are ripe because they do not “slip” like muskmelons. Actually, there is one variety that does slip called Earlidew, but it is the exception to the rule. Ripe honeydew melons become soft on the flower end of the fruit. The “flower end” is the end opposite where the stem attaches. Also, honeydews should change to a light or yellowish color when ripe, but this varies with variety. (Ward Upham)

Fruit:

Watering Fruit Plants in Hot Summers

The stress may also reduce the development of fruit buds for next year's fruit crop. If you have fruit plants such as trees, vines, canes, and such, check soil moisture at the roots. Insert a spade or shovel or a pointed metal or wood probe -- a long screwdriver works well for this. Shove these into the soil about 8 to 12 inches. If the soil is hard, dry, and difficult to penetrate, the moisture level is very low, and plants should be irrigated to prevent drooping and promote fruit enlargement. Water can be added to the soil using sprinklers, soaker hose, drip irrigation, or even a small trickle of water running from the hose for a few hours. The amount of time you irrigate should depend upon the size of plants and the volume of water you are applying. Add enough moisture so you can easily penetrate the soil in the root area of the plant with a metal rod, wooden dowel or other probe to a depth of 12 inches. When hot, dry weather continues, continue to check soil moisture at least once a week.

Strawberries have a shallow root system and may need to be watered more often – maybe twice a week during extreme weather. Also, newly planted fruit trees sited on sandy soils may also need water twice a week. (Ward Upham)

Pests:

Cicada Killer Wasps

Although these wasps are huge, they usually ignore people. Males may act aggressively if they are threatened, but are unable to sting. Females can sting, but are so passive that they rarely do. Even if they do sting, the pain is less than

that of smaller wasps such as the yellow jacket or paper wasp and is similar to the sting of a sweat bee.

The cicada killer is a solitary wasp rather than a social wasp like the yellow jacket. The female nests in burrows in the ground. These burrows are quarter-size in diameter and can go 6 inches straight down and another 6 inches horizontally. Adults normally live 60 to 75 days from mid-July to mid-September and feed on flower nectar and sap. The adult female seeks cicadas on the trunks and lower limbs of trees. She stings her prey, flips it over, straddles it and carries it to her burrow. If she has a tree to climb, she will climb the tree so she can get airborne and fly with cicada back to the nest. If not, she will drag it. She will lay one egg per cicada if the egg is left unfertilized. Unfertilized eggs develop into males only. Fertilized eggs develop into females and are given at least two cicadas. Cicadas are then stuffed into the female’s burrow. Each burrow normally has three to four cells with one to two cicadas in each. However, it is possible for one burrow to have 10 to 20 cells.

Eggs hatch in two to three days, and larvae begin feeding on paralyzed cicadas. Feeding continues for four to 10 days until only the outer shell of the cicada remains. The larva overwinters inside a silken case. Pupation occurs in the spring. There is one generation per year. Cicada killers are not dangerous, but they can be a nuisance. If you believe control is necessary, treat the burrows after dark to ensure the female wasps are in their nests. The males normally roost on plants near burrow sites. They can be captured with an insect net or knocked out of the air with a tennis racket during the day. Carbaryl (Sevin) or permethrin may be used for control. (Ward Upham)

Fall Webworm

Mature caterpillars are yellowish with black and brown markings, and have many tufts of long hair. As larvae mature, they crawl down the tree and spend the winter as pupa in the leaf litter under the tree.

High populations of fall webworm can completely defoliate host plants but do not kill them. However, on pecan trees, nut production and quality can be reduced if webworms are not controlled. On ornamental plants, control is optional.

Pruning and destroying the infested portions of branches is a common control practice while webs are still small. Also, a stick or pole with a nail inserted crosswise can be used to snag individual webs. Twisting the pole after insertion will cause the web to wrap around the pole where it can be removed and destroyed. Instead of a nail inserted crosswise, some people use a toilet brush attached to the end of a pole. Insecticides can also be used for control but a commercial quality, high-pressure sprayer is needed to penetrate the webs. Numerous products can be used for control including spinosad (Conserve; Fertilome Borer, Bagworm, Leafminer and Tent Caterpillar Spray; Captain Jack’s Dead Bug Brew),

cyfluthrin (Tempo, Bayer Vegetable & Garden Insect Spray) and permethrin (numerous trade names). We normally consider fall webworm damage to be purely aesthetic, and control is not needed to protect the health of the tree. (Ward Upham)

Contributors: Ward Upham, Extension Associate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed